Tytan (księżyc)

Zdjęcie Tytana wykonane przez sondę Cassini, w naturalnych barwach. | |

| Planeta | |

|---|---|

| Odkrywca | |

| Data odkrycia | 25 marca 1655 |

| Charakterystyka orbity | |

| Półoś wielka | 1 221 865 km[1] |

| Mimośród | 0,0288[1] |

| Okres obiegu | 15,945 d[1] |

| Nachylenie do płaszczyzny Laplace’a | 0,306°[1] |

| Długość węzła wstępującego | 28,060°[1] |

| Argument perycentrum | 180,532°[1] |

| Anomalia średnia | 163,310°[1] |

| Własności fizyczne | |

| Średnica równikowa | 5150 km |

| Powierzchnia | 8,3 ×107 km² |

| Masa | 1,345 ×1023 kg |

| Średnia gęstość | 1,88 g/cm³ |

| Przyspieszenie grawitacyjne na powierzchni | 1,35 m/s² |

| Prędkość ucieczki | 2,639 km/s |

| Okres obrotu wokół własnej osi | |

| Albedo | 0,22 |

| Jasność obserwowana (z Ziemi) | |

| Temperatura powierzchni | 93,7 K |

| Ciśnienie atmosferyczne | 146,7 kPa |

| Skład atmosfery | 98,4% azot |

Tytan (Saturn VI) – największy księżyc Saturna, jedyny w Układzie Słonecznym otoczony gęstą atmosferą, w której zachodzą skomplikowane zjawiska pogodowe. Jest to również jedyne ciało poza Ziemią, na którym odkryto powierzchniowe zbiorniki cieczy – jeziora ciekłego metanu.

Nazwa

Tytan został odkryty w 1655 roku przez Christiaana Huygensa, jako pierwszy z satelitów Saturna. Nazwa pochodzi od tytanów z mitologii greckiej.

Właściwości fizyczne

Tytan jest drugim pod względem wielkości księżycem w Układzie Słonecznym, większym od Merkurego – najmniejszej planety w naszym układzie. Do przybycia sondy Voyager 1 w 1980 r. uważano, że jest nawet większy od Ganimedesa, jednak kiedy została odkryta atmosfera Tytana, okazało się, że ma nieznacznie mniejszą średnicę.

Atmosfera

Niektóre księżyce w Układzie Słonecznym, np. księżyce galileuszowe, mają nikłą otoczkę gazową. Jednak jedynie Tytan ma gęstą atmosferę, gęstszą od ziemskiej. Ma ona pomarańczowy kolor i jest nieprzejrzysta w szerokim zakresie fal elektromagnetycznych (w tym w zakresie widzialnym). Jej istnienie jako pierwszy zasugerował w 1907 roku Josep Comas Solá, a potwierdził w 1944 roku Gerard Kuiper.

Atmosfera składa się głównie z azotu z domieszką argonu, metanu i innych związków organicznych, takich jak etan i acetylen, które powstają w górnych warstwach atmosfery w wyniku oddziaływania na metan słonecznego promieniowania ultrafioletowego. Związki chemiczne w atmosferze Tytana przepuszczają jedynie około 10% promieni słonecznych, przy czym atmosfera jest niemal całkowicie przepuszczalna dla średniej (termalnej) podczerwieni, co prowadzi do obniżenia temperatury powierzchni. Efekt ten jest kompensowany z nawiązką przez efekt cieplarniany, związany z wysoką zawartością metanu. Ciśnienie przy powierzchni wynosi 1,5 bara, czyli jest o 50% większe niż na Ziemi. Podczas lądowania próbnika Huygens zmierzono także prędkość wiatru, która wynosiła 60 km/h. Badania atmosfery tego ciała niebieskiego są szczególnie interesujące ze względu na jej podobieństwo do ziemskiej atmosfery sprzed około czterech miliardów lat. Grubość atmosfery Tytana szacuje się na od 200 do 880 km. Tytan nie ma własnego pola magnetycznego, a magnetosfera Saturna chroni go przed wiatrem słonecznym tylko częściowo.

Pomimo ograniczonego dostępu światła, na powierzchni Tytana panuje wyraźny cykl dobowy. W ciągu dnia Słońce nagrzewa powierzchnię, co ma znaczący wpływ na jego atmosferę. W atmosferze jest kilka wyraźnie oddzielonych warstw przypominających atmosferę Ziemi. Najniższa część podzielona jest na dwie warstwy graniczne. Grubość niższej zmienia się w cyklu dziennym, co powodowane jest ogrzewaniem powierzchni Tytana. Grubość wyższej warstwy granicznej zmienia w dłuższym cyklu i wpływa ona na klimat panujący na Tytanie[3].

Budowa wewnętrzna

Tytan jest zaliczany do księżyców lodowych, jako że składa się w dużej mierze z lodu wodnego. Pod kilkukilometrowej grubości lodową skorupą znajduje się prawdopodobnie warstwa ciekłej wody, przypominająca podpowierzchniowe oceany na Europie i Ganimedesie. Jeszcze głębiej jest warstwa wysokociśnieniowego lodu VI i jądro złożone ze skał o dużej zawartości wody, którego średnicę szacuje się na około 2000 km[4].

Powierzchnia

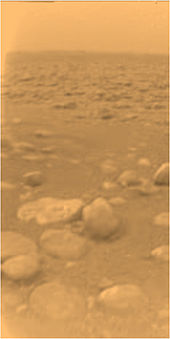

Obserwacje powierzchni Tytana są utrudnione z powodu gęstej i nieprzezroczystej atmosfery. Dzięki misji sondy Cassini udało się uzyskać wiele istotnych danych, a także wykonać pierwsze zdjęcia powierzchni księżyca. Do najciekawszych zaobserwowanych tam struktur należą:

- Jeziora ciekłego metanu w obszarach podbiegunowych. Ich obecność podejrzewano od dawna. Naukowcy mieli nadzieję, że lądownik Huygens wyląduje w jednym ze zbiorników, co jednak nie nastąpiło. Niemniej jednak na wielu zdjęciach wykonanych podczas lądowania widać struktury, które najprawdopodobniej są jeziorami płynnych węglowodorów. Te ciemne obszary mogą jednak być także pozostałościami po takich zbiornikach, które w niedawnej przeszłości wyparowały. Aby potwierdzić którąś z teorii, potrzebne są obserwacje długoterminowe, gdyż opady atmosferyczne występują sezonowo, a pory roku na Tytanie trwają wiele lat ziemskich.

- Na zdjęciach ukazujących ciemne obszary widać także ciemne kanały, przecinające obszary o jasnej barwie. Są to najprawdopodobniej węglowodorowe rzeki i strumienie. Sugeruje to ich kształt, rozgałęzienia tworzące sieć dopływów i ujścia wychodzące w kierunku ciemnych obszarów, o charakterze delty rzecznej. Niektóre z takich kanałów mają 100 kilometrów długości.

- W okolicach biegunów zaobserwowano duże ciemne formacje, również będące jeziorami węglowodorów. Największe z nich, Kraken Mare, jest wielkości Morza Kaspijskiego i w skali księżyca jest prawdziwym morzem. Nie zostało jeszcze sfotografowane w całości. Na zdjęciu widać również wyspy, w tym łańcuch wysp będący wyraźnym przedłużeniem grzbietu wzgórz widocznych na brzegu.

- Na kilku zdjęciach zaobserwowano twory, które kształtem przypominają wulkany. Mogą to być kriowulkany wyrzucające z siebie mieszaninę lodu wodnego i metanu. Dla ich istnienia kluczowe jest źródło energii. Być może wnętrze podgrzewają siły pływowe Saturna. Potwierdzeniem aktywności wulkanicznej jest obecność argonu w atmosferze.

- Jest niewiele kraterów uderzeniowych, co sugeruje, że powierzchnia jest geologicznie młoda.

- W okolicach równika sonda Cassini zaobserwowała ciągnące się przez setki kilometrów wydmy. Ich wysokość dochodzi do 100 m. Wydmy zostały ukształtowane przez zmienne, łagodne wiatry. Podczas gdy wiatry na Ziemi wynikają z nierównomiernego ogrzewania powierzchni przez Słońce, na Tytanie usypują je raczej wiatry o charakterze pływowym wywołane przyciąganiem Saturna. Nie są one uformowane z piasku, ale z drobin wodnego lodu lub związków organicznych.

Klimat

Temperatura powierzchni Tytana wynosi ok. −179,2 °C. W tej temperaturze wodny lód sublimuje przy bardzo niskim ciśnieniu, przez co w stratosferze są śladowe ilości pary wodnej[6]. Do Tytana dociera 1% światła słonecznego, które otrzymuje Ziemia[7]. Ponadto 90% światła jest absorbowane przez gęstą atmosferę. Ostatecznie do powierzchni Tytana dociera 0,1% światła, jakie otrzymuje powierzchnia Ziemi[8].

Metan zawarty w atmosferze powoduje na powierzchni księżyca efekt cieplarniany, bez którego Tytan byłby dużo zimniejszy[9]. Z kolei zmętnienie jego atmosfery przyczynia się do przeciwnego efektu – odbijając promienie słoneczne z powrotem w przestrzeń kosmiczną, niweluje częściowo efekt cieplarniany. W rezultacie temperatura powierzchni jest znacznie niższa niż temperatura górnych warstw atmosfery[10].

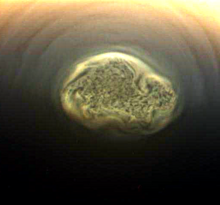

Chmury Tytana, prawdopodobnie utworzone z metanu i etanu są rozproszone i zmienne, wyróżniając się na tle zmętnienia[12]. Badania przeprowadzone przez sondę Huygens wskazały, że w atmosferze Tytana występują okresowe deszcze ciekłego metanu i innych związków organicznych[13].

Chmury przeważnie pokrywają 1% powierzchni księżyca, jednak zaobserwowano gwałtowne zwiększanie się pokrywy chmur do 8% powierzchni. Według jednej z hipotez południowe chmury tworzą się, gdy zwiększony poziom nasłonecznienia podczas pory letniej na południowej półkuli tworzy wypiętrzenia w atmosferze, prowadzące do konwekcji. Jednak formowanie chmur zostało zaobserwowane nie tylko po okresie przesilenia letniego na południowej półkuli, lecz także w środku pory wiosennej. Zwiększone stężenie metanu na biegunie południowym prawdopodobnie przyczyniło się do szybkiego wzrostu zachmurzenia[14]. Lato na południowej półkuli Tytana trwało do 2010 roku, po czym, w wyniku ruchu Saturna po orbicie, rozpoczęło się na półkuli północnej[15]. W miarę zmian pór roku etan przypuszczalnie zacznie się skraplać nad biegunem południowym[16].

Badania Tytana

- 12 listopada 1980 roku w pobliże Saturna dotarła sonda Voyager 1. Jej trajektorię zaplanowano tak, by przeleciała 4000 kilometrów od Tytana, co spowodowało wyrzucenie sondy poza płaszczyznę ekliptyki. Naukowcy sądzili, że będą mogli dostrzec powierzchnię księżyca. Jednak atmosfera była zbyt gęsta, a sondy nie wyposażono w urządzenia, które mogłyby ją przeniknąć. Dopiero po ponad 20 latach wykazano, że staranna obróbka zdjęć pozwala jednak dojrzeć niektóre wielkoskalowe struktury powierzchni[17].

- 1 lipca 2004 roku do Saturna doleciała sonda Cassini. Głównym celem lądownika Huygens, wykonanego przez ESA, było zebranie danych dotyczących gęstej atmosfery. 14 stycznia 2005 roku, po około 2,5-godzinnym opadaniu[18] wylądował z powodzeniem na Tytanie[19][20]. Próbnik w trakcie opadania wykonywał zdjęcia i nagrywał dźwięki. Huygens po lądowaniu i krótkim ślizgu natrafił na miękkie, zakurzone podłoże[18]. Po ponad godzinie zakończył pracę i zamarzł (przewidywany czas pracy wynosił kilkanaście minut). Zdjęcia wykonane przez próbnik w trakcie lądowania ukazały struktury przypominające systemy rzeczne na Ziemi[18]. W próbniku zainstalowano m.in. aparaturę pomiarową produkcji polskiej (termometr).

Sonda Cassini kontynuowała badania Tytana podczas kolejnych przelotów. Zwykle nie zbliżała się na mniej niż około 950 km, ze względu na atmosferę rozciągającą się nawet do wysokości 975 km, która zaburzała prowadzenie obserwacji. Sonda była najbliżej Tytana (880 km[21]) 21 czerwca 2010 roku. Ten przelot został wykonany dla sprawdzenia, czy Tytan ma własne pole magnetyczne[18].

W roku 2004, na północnym biegunie Tytana sonda Cassini zarejestrowała wysoko unoszące się mgły oraz wirującą chmurę. W pierwszej połowie 2012 roku, podczas kolejnych przelotów obok Tytana, stwierdzono obecność podobnej struktury nad południowym biegunem księżyca. Według naukowców z programu Cassini, to zmienne oświetlenie Tytana – czyli pory roku – powoduje zmiany w atmosferze księżyca[18].

Życie na Tytanie

Istnienie organizmów żywych jest mało prawdopodobne, głównie ze względu na ekstremalnie niskie temperatury, pomimo dużej ilości związków organicznych. Źródłem energii mogłyby być węglowodory produkowane w górnych warstwach atmosfery, które dostarczają wystarczającą ilość energii, by ewentualne organizmy mogły wytworzyć ciekłe środowisko w swoim wnętrzu, pozwalające na zachodzenie wielu reakcji chemicznych niezbędnych do życia.

NASA planuje na połowę lat 30. XXI wieku misję kosmiczną Dragonfly, w ramach której zasilany radioizotopowo dron zbada potencjalne sprzyjające życiu miejsca na powierzchni Tytana[22][23].

Zobacz też

- Ukształtowanie powierzchni Tytana

- Chronologiczny wykaz odkryć planet, planet karłowatych i ich księżyców w Układzie Słonecznym

- Księżyce Saturna – zestawienie podstawowych danych

- Inne duże księżyce Saturna: Rea, Japet, Dione, Tetyda i Enceladus

Przypisy

- ↑ a b c d e f g Planetary Satellite Mean Orbital Parameters (ang.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory, 2013-08-23. [dostęp 2016-02-22].

- ↑ Classic Satellites of the Solar System. Observatorio ARVAL. [dostęp 2010-06-28]. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2018-12-25)].

- ↑ Becky Crew: Climate cycle reveals Titan as Earth-like (ang.). 2012-01-16. [dostęp 2012-01-18]. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2012-04-21)].

- ↑ Layers of Titan -- Annotated (ang.). W: Cassini Solstice Mission [on-line]. NASA, 2012-02-23. [dostęp 2012-04-27]. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2015-09-14)].

- ↑ Tortola Facula. W: Cassini Solstice Mission [on-line]. NASA, 2011-07-07. [dostęp 2011-12-06]. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2011-04-19)].

- ↑ V. Cottini i inni, Water vapor in Titan’s stratosphere from Cassini CIRS far-infrared spectra, „Icarus”, 2, 220, 2012, s. 855–862, DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2012.06.014, ISSN 0019-1035, Bibcode: 2012Icar..220..855C.

- ↑ Titan: A World Much Like Earth. Space.com, 2009-08-06. [dostęp 2012-04-02].

- ↑ Faint sunlight enough to drive weather, clouds on Saturn’s moon Titan Between the large distance from the Sun and the thick atmosphere, Titan’s surface receives about 0.1 percent of the solar energy that Earth does.

- ↑ Titan Has More Oil Than Earth. luty 13, 2008. [dostęp 2008-02-13].

- ↑ C.P. McKay, J.B. Pollack, R. Courtin. The greenhouse and antigreenhouse effects on Titan. „Science”. 253 (5024), s. 1118–1121, 1991. DOI: 10.1126/science.11538492. PMID: 11538492.

- ↑ Preston Dyches: Cassini Tracks Clouds Developing Over a Titan Sea. W: NASA [on-line]. 2014-08-12. [dostęp 2014-08-13].

- ↑ Bill Arnett: Titan. W: Nine planets [on-line]. University of Arizona, Tucson, 2005. [dostęp 2005-04-10]. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2005-11-21)].

- ↑ Emily Lakdawalla, Titan: Arizona in an Icebox?, The Planetary Society, 21 stycznia 2004 [dostęp 2005-03-28] [zarchiwizowane z adresu 2010-02-12].

- ↑ Schaller Emily L. i inni, A large cloud outburst at Titan’s south pole [PDF], „Icarus”, 1, 182, 2006, s. 224–229, DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2005.12.021, Bibcode: 2006Icar..182..224S [dostęp 2007-08-23].

- ↑ The Way the Wind Blows on Titan, JPL, 1 czerwca 2007 [dostęp 2007-06-02] [zarchiwizowane z adresu 2009-04-27].

- ↑ David Shiga. Huge ethane cloud discovered on Titan. „New Scientist”. 313, s. 1620, 2006. [dostęp 2007-08-07].

- ↑ James Richardson, Ralph D. Lorenz, Alfred McEwen. Titan’s surface and rotation: new results from Voyager 1 images. „Icarus”. 170, s. 113–124, 2004. DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2004.03.010.

- ↑ a b c d e Kamil Złoczewski: Niezwykła atmosfera Tytana. Księżyc pełen niespodzianek. Poznań: Amermedia, 2013, s. 4, seria: Kosmos. Tajemnice Wszechświata. Encyklopedia Astronomii i Astronautyki. ISBN 978-83-252-1917-8.

- ↑ Kalendarium dziejów świata. Współczesność : od 1945, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 2008, s. 87, ISBN 978-83-01-15379-3.

- ↑ Jerzy Gronkowski (tłum.), Gwiazdy i planety, 2007, s. 201, ISBN 83-7512-226-2.

- ↑ Cassini. W: Loty kosmiczne [on-line]. [dostęp 2016-02-08].

- ↑ JHUAPL proponuje misję Dragonfly do Tytana. Puls Kosmosu, 2017-08-24. [dostęp 2019-01-23].

- ↑ Krzysztof Kanawka: Dragonfly – prezentacja koncepcji misji. Kosmonauta.net, 18 stycznia 2019. [dostęp 2019-01-23].

Linki zewnętrzne

- zdjęcia z misji Huygens-Cassini (ang.)

- tytanowy wiatr (mp3) (ang.)

- Titan (ang.). W: Solar System Exploration [on-line]. NASA. [dostęp 2016-02-08].

Media użyte na tej stronie

This is a revised version of Solar_System_XXIX.png.

Seasonal changes in the atmosphere of Saturn's largest moon are captured in this natural-colour image which shows Titan with a slightly darker top half and a slightly lighter bottom half. Titan's atmosphere has a seasonal hemispheric dichotomy, and this image was taken shortly after Saturn's August 2009 equinox. Images taken using red, green and blue spectral filters were combined to create this natural-colour view. Scientists have found that the winter hemisphere typically appears to have more high-altitude haze, making it darker at shorter wavelengths (ultraviolet through blue) and brighter at infra-red wavelengths. The switch between dark and bright occurred over the course of a year or two around the last equinox. Scientists are studying the mechanism responsible for this change, and will monitor the dark-light difference as it flip-flops now that the 2009 equinox has signalled the coming of spring and then summer in the northern hemisphere. Although this hemispheric boundary appears to run directly east-west near the equator, its position is not level with latitude and is actually offset from the equator by about 10 degrees of latitude. This view looks toward the Saturn-facing side of Titan (5150 kilometres across). North on Titan is up. The images were obtained with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera at a distance of approximately 174,000 kilometres from Titan. Image scale is 10 kilometres per pixel.

This colorized mosaic from NASA's Cassini mission shows the most complete view yet of Titan's northern land of lakes and seas. Saturn's moon Titan is the only world in our solar system other than Earth that has stable liquid on its surface. The liquid in Titan's lakes and seas is mostly methane and ethane.

The data were obtained by Cassini's radar instrument from 2004 to 2013. In this projection, the north pole is at the center. The view extends down to 50 degrees north latitude. In this color scheme, liquids appear blue and black depending on the way the radar bounced off the surface. Land areas appear yellow to white. A haze was added to simulate the Titan atmosphere.

Kraken Mare, Titan's largest sea, is the body in black and blue that sprawls from just below and to the right of the north pole down to the bottom right. Ligeia Mare, Titan's second largest sea, is a nearly heart-shaped body to the left and above the north pole. Punga Mare is just below the north pole.

The area above and to the left of the north pole is dotted with smaller lakes. Lakes in this area are about 30 miles (50 kilometers) across or less.

Most of the bodies of liquid on Titan occur in the northern hemisphere. In fact nearly all the lakes and seas on Titan fall into a box covering about 600 by 1,100 miles (900 by 1,800 kilometers). Only 3 percent of the liquid at Titan falls outside of this area.

Scientists are trying to identify the geologic processes that are creating large depressions capable of holding major seas in this limited area. A prime suspect is regional extension of the crust, which on Earth leads to the formation of faults creating alternating basins and roughly parallel mountain ranges. This process has shaped the Basin and Range province of the western United States, and during the period of cooler climate 13,000 years ago much of the present state of Nevada was flooded with Lake Lahontan, which (though smaller) bears a strong resemblance to the region of closely packed seas on Titan.

A related flyover can be seen at PIA17656.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington, DC. The Cassini orbiter was designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The radar instrument was built by JPL and the Italian Space Agency, working with team members from the United States and several European countries.

For more information about the Cassini-Huygens mission visit http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov and http://www.nasa.gov/cassini.

The original NASA image has been modified by rotating 90 deg. clockwise and cropping.

Some of the features in this image have been annotated in Wikimedia Commons.This true color picture was assembled from Voyager 2 Saturn images obtained Aug. 4 [1981] from a distance of 21 million kilometers (13 million miles) on the spacecraft's approach trajectory. Three of Saturn's icy moons are evident at left. They are, in order of distance from the planet: Tethys, 1,050 km. (652 mi.) in diameter; Dione, 1,120 km. (696 mi.); and Rhea, 1,530 km. (951 mi.). The shadow of Tethys appears on Saturn's southern hemisphere. A fourth satellite, Mimas, is less evident, appearing as a bright spot a quarter-inch in in from the planet's limb about half an inch above Tethys; the shadow of Mimas appears on the planet about three-quarters of an inch directly above that of Tethys. The pastel and yellow hues on the planet reveal many contrasting bright and darker bands in both hemispheres of Saturn's weather system. The Voyager project is managed for NASA by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California, United States.

Tortola Facula (formerly interpreted as cryovolcano) on Saturn moon Titan in false color, taken by the Cassini space probe with ultraviolet and infrared camera.

Clouds Over Ligeia Mare on Titan

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/spaceimages/details.php?id=PIA18420

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?release=2014-274

Click here for full animation of PIA18420 Click on the image for the full animation http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/archive/PIA18420.gif

This animated sequence of Cassini images shows methane clouds moving above the large methane sea on Saturn's moon Titan known as Ligeia Mare.

The spacecraft captured the views between July 20 and July 22, 2014, as it departed Titan following a flyby. Cassini tracked the system of clouds as it developed and dissipated over Ligeia Mare during this two-day period. Measurements of the cloud motions indicate wind speeds of around 7 to 10 miles per hour (3 to 4.5 meters per second).

The timing between exposures in the sequence varies. In particular, there is a 17.5-hour jump between the second and third frames. Most other frames are separated by one to two hours.

A separate view, PIA18421, shows the location of these clouds relative to features in Titan's north polar region.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington. The Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras were designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The imaging operations center is based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo.

For more information about the Cassini-Huygens mission visit http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov and http://www.nasa.gov/cassini. The Cassini imaging team homepage is at http://ciclops.org.Titan, the second-largest moon in the Solar System, has a permanent hurricane at its south pole. "Warm" air goes up the sides, gets even colder, and sinks down the center.

Saturn Cassini-Huygens (NASA)

Instrument: Imaging Science Subsystem - Narrow Angle

Saturn's peaceful beauty invites the Cassini spacecraft for a closer look in this natural color view, taken during the spacecraft's approach to the planet. By this point in the approach sequence, Saturn was large enough that two narrow angle camera images were required to capture an end-to-end view of the planet, its delicate rings and several of its icy moons. The composite is made entire from these two images.

Moons visible in this mosaic: Epimetheus (116 kilometers, 72 miles across), Pandora (84 kilometers, 52 miles across) and Mimas (398 kilometers, 247 miles across) at left of Saturn; Prometheus (102 kilometers, 63 miles across), Janus (181 kilometers, 113 miles across) and Enceladus (499 kilometers, 310 miles across) at right of Saturn.

The images were taken on May 7, 2004 from a distance of 28.2 million kilometers (17.6 million miles) from Saturn. The image scale is 169 kilometers (105 miles) per pixel. Moons in the image have been brightened for visibility.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the Cassini-Huygens mission for NASA's Office of Space Science, Washington, D.C. The Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras, were designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The imaging team is based at the Space Science Institute, Boulder, Colo.

For more information, about the Cassini-Huygens mission visit, http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov and the Cassini imaging team home page, http://ciclops.org.PIA19657: Titan Polar Maps - 2015 - North Pole

http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19657

The northern and southern hemispheres of Titan are seen in these polar stereographic maps, assembled in 2015 using the best-available images of the giant Saturnian moon from NASA's Cassini mission. The images were taken by Cassini's imaging cameras using a spectral filter centered at 938 nanometers, allowing researchers to examine variations in albedo (or inherent brightness) across the surface of Titan. These maps utilize imaging data collected through Cassini's flyby on April 7, 2014, known as "T100."

Titan's north pole was not well illuminated early in Cassini's mission, because it was winter in the northern hemisphere when the spacecraft arrived at Saturn. Cassini has been better able to observe northern latitudes in more recent years due to seasonal changes in solar illumination. Compared to the previous version of Cassini's north polar map (see PIA11146), this map provides much more detail and fills in a large area of missing data. The imaging data in these maps complement Cassini synthetic aperture radar (SAR) mapping of Titan's north pole (see PIA17655).

The uniform gray area in the northern hemisphere indicates a gap in the imaging coverage of Titan's surface, to date. The missing data will be imaged by Cassini during flybys on December 15, 2016 and March 5, 2017.

Lakes are also seen in the southern hemisphere map, but they are much less common than in the north polar region. Only a lakes have been confirmed in the south. The dark, footprint-shaped feature at 180 degrees west is Ontario Lacus; a smaller lake named Crveno Lacus can be seen as a very dark spot just above Ontario. The dark-albedo area seen at the top of the southern hemisphere map (at 0 degrees west) is an area called Mezzoramia.

Each map is centered on one of the poles, and surface coverage extends southward to 60 degrees latitude. Grid lines indicate latitude in 10-degree increments and longitude in 30-degree increments. The scale in the full-size versions of these maps is 4,600 feet (1,400 meters) per pixel. The mean radius of Titan used for projection of these maps is 1,600 miles (2,575 kilometers).

The Cassini mission is a cooperative project of NASA, ESA (the European Space Agency) and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington. The Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras were designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The imaging operations center is based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

For more information about the Cassini-Huygens mission visit http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov and http://www.nasa.gov/cassini. The Cassini imaging team homepage is at http://ciclops.org.This poster is a stereographic (fish-eye) projection taken with the descent imager/spectral radiometer onboard the European Space Agency's Huygens probe, when the probe was about 5 kilometers (3 miles) above Titan's surface. The images were taken on Jan. 14, 2005. The Huygens probe was delivered to Saturn's moon Titan by the Cassini spacecraft, which is managed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. NASA supplied two instruments on the probe, the descent imager/spectral radiometer and the gas chromatograph mass spectrometer.

PIA19657: Titan Polar Maps - 2015 - South Pole

http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19657

The northern and southern hemispheres of Titan are seen in these polar stereographic maps, assembled in 2015 using the best-available images of the giant Saturnian moon from NASA's Cassini mission. The images were taken by Cassini's imaging cameras using a spectral filter centered at 938 nanometers, allowing researchers to examine variations in albedo (or inherent brightness) across the surface of Titan. These maps utilize imaging data collected through Cassini's flyby on April 7, 2014, known as "T100."

Titan's north pole was not well illuminated early in Cassini's mission, because it was winter in the northern hemisphere when the spacecraft arrived at Saturn. Cassini has been better able to observe northern latitudes in more recent years due to seasonal changes in solar illumination. Compared to the previous version of Cassini's north polar map (see PIA11146), this map provides much more detail and fills in a large area of missing data. The imaging data in these maps complement Cassini synthetic aperture radar (SAR) mapping of Titan's north pole (see PIA17655).

The uniform gray area in the northern hemisphere indicates a gap in the imaging coverage of Titan's surface, to date. The missing data will be imaged by Cassini during flybys on December 15, 2016 and March 5, 2017.

Lakes are also seen in the southern hemisphere map, but they are much less common than in the north polar region. Only a lakes have been confirmed in the south. The dark, footprint-shaped feature at 180 degrees west is Ontario Lacus; a smaller lake named Crveno Lacus can be seen as a very dark spot just above Ontario. The dark-albedo area seen at the top of the southern hemisphere map (at 0 degrees west) is an area called Mezzoramia.

Each map is centered on one of the poles, and surface coverage extends southward to 60 degrees latitude. Grid lines indicate latitude in 10-degree increments and longitude in 30-degree increments. The scale in the full-size versions of these maps is 4,600 feet (1,400 meters) per pixel. The mean radius of Titan used for projection of these maps is 1,600 miles (2,575 kilometers).

The Cassini mission is a cooperative project of NASA, ESA (the European Space Agency) and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington. The Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras were designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The imaging operations center is based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

For more information about the Cassini-Huygens mission visit http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov and http://www.nasa.gov/cassini. The Cassini imaging team homepage is at http://ciclops.org.Warstwy tworzące wnętrze Tytana, największego księżyca Saturna.

Diameter comparison of Titan, Moon, and Earth.

Scale: Approximately 29km per pixel.

PIA19658: Titan Global Map - June 2015

http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA19658

This global digital map of Saturn's moon Titan was created using images taken by the Cassini spacecraft's imaging science subsystem (ISS). The map was produced in June 2015 using data collected through Cassini's flyby on April 7, 2014, known as "T100."

The images were taken using a filter centered at 938 nanometers, allowing researchers to examine variations in albedo (or inherent brightness) across the surface of Titan. Because of the scattering of light by Titan's dense atmosphere, no topographic shading is visible in these images.

The map is an equidistant projection and has a scale of 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) per pixel. Actual resolution varies greatly across the map, with the best coverage (close to the map scale) along the equator near the center of the map at 180 degrees west longitude. The lowest resolution coverage can be seen in the northern mid-latitudes on the sub-Saturn hemisphere.

Mapping coverage in the northern polar region has greatly improved since the previous version of this map in 2011 (see PIA14908). Large dark areas, now known to be liquid-hydrocarbon-filled lakes and seas, have since been documented at high latitudes. Titan's north pole was not well illuminated early in Cassini's mission, because it was winter in the northern hemisphere when the spacecraft arrived at Saturn. Cassini has been better able to observe northern latitudes in more recent years due to seasonal changes in solar illumination.

This map is an update to the previous versions released in April 2011 and February 2009 (see PIA11149). Data from the past four years (the most recent data in the map is from April 2014) has completely filled in missing data in the north polar region and replaces the earlier imagery of the Xanadu region with higher quality data. A data gap of about 3 to 5 percent of Titan's surface still remains, located in the northern mid-latitudes on the sub-Saturn hemisphere of Titan.

The uniform gray area in the northern hemisphere indicates a gap in the imaging coverage of Titan's surface, to date. The missing data will be imaged by Cassini during flybys on December 15, 2016 and March 5, 2017.

The mean radius of Titan used for projection of this map is 1,600 miles (2,575 kilometers). Titan is assumed to be spherical until a control network -- a model of the moon's shape based on multiple images tied together at defined points on the surface -- is created at some point in the future.

The Cassini mission is a cooperative project of NASA, ESA (the European Space Agency) and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington. The Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras were designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The imaging operations center is based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

For more information about the Cassini–Huygens mission visit http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov and http://www.nasa.gov/cassini. The Cassini imaging team homepage is at http://ciclops.org.