Zapalenie aorty

| Aortitis | |

Angiogram ukazujący zespół Takayasu, jedną z przyczyn zapalenia aorty | |

| ICD-10 | I79.1 |

|---|---|

Zapalenie aorty (łac. aortitis) – stan zapalny obejmujący ścianę aorty[1][2].

Epidemiologia

Badanie przeprowadzone w Danii wykazało, że w 6,1% preparatach resekowanej z różnych powodów aorty wstępującej stwierdzono zapalenie aorty, a w 76% były to zapalenia idiopatyczne[1]. Inne badanie przeprowadzone w Japonii określiło częstość występowania na 0,01 na 100 000 dzieci na rok[2].

Etiologia

Przyczynami choroby są choroby zakaźne i autoimmunologiczne[2]. Zapalenie aorty w dużej części przypadków jest idiopatyczne[3][4].

Najczęstszymi nieinfekcyjnymi przyczynami zapalenia aorty są zapalenia dużych naczyń – olbrzymiokomórkowe zapalenie tętnic (subkliniczne zapalenie aorty występuje u 20-65% osób z rozpoznaniem) i zespół Takayasu[5][6][2][7][8][9][10]. Istotną przyczyną zapalenia aorty są czynniki infekcyjne. W 60% przypadków infekcyjnego zapalenia aorty przyczyną są Gram-dodatnie ziarniniaki: gronkowce, enterokoki i dwoinka zapalenia płuc[11]. Do przyczyn zapalenia aorty zalicza się[2][7][12][13][14][15]:

- choroby autoimmunologiczne:

- olbrzymiokomórkowe zapalenie tętnic

- zespół Takayasu

- zespół Cogana[16]

- choroba Behçeta[17]

- reumatoidalne zapalenie stawów

- toczeń rumieniowaty układowy[18]

- zesztywniające zapalenie stawów kręgosłupa[19]

- ziarniniakowatość z zapaleniem naczyń (w tym zespół Churga-Strauss)

- guzkowe zapalenie tętnic

- mikroskopowe zapalenie naczyń

- zespół Reitera[20]

- sarkoidoza

- polimialgia reumatyczna

- czynniki infekcyjne[21][22]:

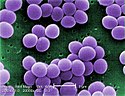

- gronkowce[23]

- dwoinka zapalenia płuc[24]

- enterokoki[11]

- salmonelloza[25]

- kiła[26][27][28]

- gruźlica (rzadka manifestacja, powstaje na skutek zakażenia z przyległych narządów lub drogą krwi)[29][30]

- inne bakterie (np. Clostridium septicum, riketsje, Haemophilus influenzae)[31][32]

- grzyby (mukormykoza, aspergiloza)[33],

- wirusy: zapalenia wątroby typu B i C, VZV, HSV

- idiopatyczne zapalenie aorty[3][34]

Objawy

Zapalenie aorty może być zarówno lekkie, jak i bardzo ciężkie[2]. Wiąże się z szerokim spektrum wywoływanych objawów, które zależą od choroby podstawowej i umiejscowienia stanu zapalnego w aorcie[2]. Podstawowe objawy to ból w klatce piersiowej, ból pleców, brzucha i gorączka, łatwa męczliwość, duszność, rzadziej tętniaki aorty, dławica piersiowa, ostry zespół wieńcowy, niedomykalność zastawki aortalnej, zakrzepica aorty oraz rozwarstwienie lub pęknięcie aorty[2][4][15]. Opisano występowanie niedokrwistości[4]. W zapaleniu aorty w olbrzymiokomórkowym zapaleniu tętnic objawy choroby podstawowej to bóle głowy oraz zaburzenia ukrwienia w obszarze unaczynienia tętnicy skroniowej, a także chromania żuchwy, polimialgia reumatyczna, bolesność skóry głowy, utrata wzroku i rzadsze zajęcie tętnic wieńcowych[2][35]. W tej chorobie zapalenie aorty jest późnym powikłaniem[35]. Pewne badanie wykazało, że spośród 168 pacjentów 30 (18%) miało tętniaka lub rozwarstwienie aorty[36]. W zespole Takayasu zwężenie aorty powyżej odejścia tętnic nerkowych lub w ich zakresie skutkuje nadciśnieniem tętniczym, występują też bóle stawów i utrata wagi[2][37]. Rzadkim powikłaniem zapalenia o tej przyczynie jest rozwarstwienie aorty[38].

Rozpoznanie

W zapaleniu aorty pomocna jest angiografia tomografu komputerowego (angio-TK), jak i angiografia rezonansu magnetycznego (angio-MR), które wypierają klasyczną angiografię. Angio-TK pozwala na rozpoznanie zwężenia aorty i dużych naczyń, obecność tętniaków oraz zakrzepicy naczynia, w ostrym okresie zapalenia uwidacznia obrzęk ściany naczynia i zapalenie tkanek położonych w okolicy aorty, ponadto ze względu na dostępność, umożliwia szybkie wykluczenie rozwarstwienia aorty. Angio-MR umożliwia rozpoznanie aktywnego zapalenia, które uwidacznia się jako obrzęk, pogrubienie lub wzmocnienie ściany naczynia. Badanie również pozwala na wykrycie powikłań zapalenia takich jak tętniaki czy zwężenia[2]. PET-TK jest przydatnym narzędziem w rozpoznawaniu i monitorowaniu aktywności olbrzymiokomórkowego zapalenia tętnic i zespołu Takayasu[2][39]. We wstępnej diagnostyce zapalenia aorty brzusznej można wykorzystać także ultrasonografię, do oceny odcinka piersiowego przydatna jest echokardiografia przezprzełykowa (TEE)[2]. OB zazwyczaj jest przyspieszony, a stężenie CRP podniesione[2][25]. Wykonuje się oznaczenie poziomu przeciwciał przeciwjądrowych, czynnika reumatoidalnego i przeciwciał przeciwko cytoplazmie neutrofilów, a także wykonuje się próbę tuberkulinową i testy na kiłę, aby określić, czy zapalenie aorty nie powstało na tle infekcyjnym[2].

Leczenie

Jeśli zachodzi podejrzenie infekcyjnego zapalenia aorty, to jeszcze przed otrzymaniem potwierdzających badań mikrobiologicznych włącza się empiryczną antybiotykoterapię, szczególnie obejmującą w spektrum działania gronkowca złocistego i Gram-ujemne pałeczki[32]. Mimo zastosowania odpowiedniego leczenia rokowanie co do przeżycia jest niskie, więc oprócz tego należy wykonać zabieg usunięcia zakażonej i martwej tkanki oraz, jeśli konieczne, resekcji tętniaka[2][32]. W przypadku autoimmunologicznego zapalenia aorty w zespole Takayasu i olbrzymiokomórkowym zapaleniu tętnic należy podawać prednizon, choć w 50% przypadków choroba nawraca[2]. Gdy występują ciężkie objawy niedokrwienia, można wykonać rewaskularyzację, a przy wtórnym nadciśnieniu angioplastykę balonową[2]. Wszczepienie stentu poprawia rokowanie[40].

Zobacz też

Przypisy

- ↑ a b Jean Schmidt i inni, Predictors for pathologically confirmed aortitis after resection of the ascending aorta: A 12-year Danish nationwide population-based cross-sectional study, „Arthritis Research & Therapy”, 13 (3), 2011, R87, DOI: 10.1186/ar3360, PMID: 21676237, PMCID: PMC3218902 (ang.).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Heather L. Gornik, Mark A. Creager, Aortitis, „Circulation”, 117 (23), 2008, s. 3039–3051, DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.760686, PMID: 18541754, PMCID: PMC2759760 (ang.).

- ↑ a b Nicolò Pipitone, Carlo Salvarani, Idiopathic aortitis: an underrecognized vasculitis, „Arthritis Research & Therapy”, 13 (4), 2011, s. 119, DOI: 10.1186/ar3389, PMID: 21787438, PMCID: PMC3239344 (ang.).

- ↑ a b c Shabneez Hussain, Salman Naseem Adil, Shahid Ahmed Sami, Anemia in a middle aged female with aortitis: a case report, „BMC Research Notes”, 8, 2015, DOI: 10.1186/s13104-015-1572-3, PMID: 26493409, PMCID: PMC4619023 (ang.).

- ↑ E. Ladich, K. Yahagi, M. E. Romero, R. Virmani. Vascular diseases: aortitis, aortic aneurysms, and vascular calcification. „Cardiovasc Pathol”. 25 (5). s. 432-441. DOI: 10.1016/j.carpath.2016.07.002. PMID: 27526100.

- ↑ I. Töpel, N. Zorger, M. Steinbauer. Inflammatory diseases of the aorta: Part 1: Non-infectious aortitis. „Gefasschirurgie”. 21 (Suppl 2). s. 80-86. DOI: 10.1007/s00772-016-0143-9. PMID: 27546992.

- ↑ a b Kimberly Weatherspoon, Wayne Gilbertie, Tara Catanzano, Emergency Computed Tomography Angiogram of the Chest, Abdomen, and Pelvis, „Seminars in ultrasound, CT, and MR”, 38 (4), 2017, s. 370–383, DOI: 10.1053/j.sult.2017.02.004, PMID: 28865527 (ang.).

- ↑ Ilkay Cinar, He Wang, James R. Stone, Clinically isolated aortitis: pitfalls, progress, and possibilities, „Cardiovascular Pathology: The Official Journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Pathology”, 29, 2017, s. 23–32, DOI: 10.1016/j.carpath.2017.04.003, PMID: 28500877 (ang.).

- ↑ J.M. Evans, W.M. O’Fallon, G.G. Hunder, Increased incidence of aortic aneurysm and dissection in giant cell (temporal) arteritis. A population-based study, „Annals of Internal Medicine”, 122 (7), 1995, s. 502–507, DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-7-199504010-00004, PMID: 7872584 (ang.).

- ↑ O. Espitia, C. Agard, Aortite et complications aortiques de l’artérite à cellules géantes (maladie de Horton), „La Revue De Medecine Interne”, 34 (7), 2013, s. 412–420, DOI: 10.1016/j.revmed.2013.02.026, PMID: 23523343 (fr.).

- ↑ a b I. Töpel, N. Zorger, M. Steinbauer. Inflammatory diseases of the aorta: Part 2: Infectious aortitis. „Gefasschirurgie”. 21 (Suppl 2). s. 87-93. DOI: 10.1007/s00772-016-0142-x. PMID: 27546993.

- ↑ Nedaa Skeik i inni, Diagnosis, Management, and Outcome of Aortitis at a Single Center, „Vascular and Endovascular Surgery”, 2017, DOI: 10.1177/1538574417704296, PMID: 28859604 (ang.).

- ↑ J. Loricera i inni, Non-infectious aortitis: a report of 32 cases from a single tertiary centre in a 4-year period and literature review, „Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology”, 33 (2 Suppl 89), 2015, s. 19–31, PMID: 25437450 (ang.).

- ↑ J. Gaudric i inni, Prise en charge chirurgicale des maladies inflammatoires de l’aorte, „La Revue De Medecine Interne”, 37 (4), 2016, s. 284–291, DOI: 10.1016/j.revmed.2015.12.017, PMID: 26797187 (fr.).

- ↑ a b G. Slobodin i inni, Aortic involvement in rheumatic diseases, „Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology”, 24 (2 Suppl 41), 2006, s. 41–47, PMID: 16859596 (ang.).

- ↑ Keisuke Sugimoto i inni, Childhood Cogan syndrome with aortitis and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated glomerulonephritis, „Pediatric Rheumatology Online Journal”, 12, 2014, s. 15, DOI: 10.1186/1546-0096-12-15, PMID: 24803850, PMCID: PMC4011777 (ang.).

- ↑ A.-C. Desbois i inni, Atteintes aortiques inflammatoires associées à la maladie de Behçet, „La Revue De Medecine Interne”, 37 (4), 2016, s. 230–238, DOI: 10.1016/j.revmed.2015.10.351, PMID: 26611428 (fr.).

- ↑ R.W. Guard i inni, Aortitis with dissection complicating systemic lupus erythematosus, „Pathology”, 27 (3), 1995, s. 224–228, PMID: 8532387 (ang.).

- ↑ C.R. Tucker i inni, Aortitis in ankylosing spondylitis: early detection of aortic root abnormalities with two dimensional echocardiography, „The American Journal of Cardiology”, 49 (4), 1982, s. 680–686, PMID: 7064818 (ang.).

- ↑ S H Morgan, R A Asherson, G R Hughes, Distal aortitis complicating Reiter's syndrome., „British Heart Journal”, 52 (1), 1984, s. 115–116, PMID: 6743420, PMCID: PMC481595 (ang.).

- ↑ Upul Pathirana i inni, Ascending aortic aneurysm caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, „BMC Research Notes”, 8, 2015, DOI: 10.1186/s13104-015-1667-x, PMID: 26553119, PMCID: PMC4638108 (ang.).

- ↑ O. Zizi, H. Jiber, A. Bouarhroum, Aortite infectieuse à Streptococcus pneumoniae, „Journal Des Maladies Vasculaires”, 41 (1), 2016, s. 36–41, DOI: 10.1016/j.jmv.2015.12.003, PMID: 26775836 (fr.).

- ↑ F. Daniel Ramirez, Bruce M. Jamison, Benjamin Hibbert, Infectious Aortitis, „International Heart Journal”, 57 (5), 2016, s. 645–648, DOI: 10.1536/ihj.16-029, PMID: 27581676 (ang.).

- ↑ Mathijs G. Buimer i inni, Endovascular repair of a Streptococcus pneumonia-induced aortitis complicated by an iliacocaval fistula, „Vascular and Endovascular Surgery”, 46 (7), 2012, s. 570–574, DOI: 10.1177/1538574412456307, PMID: 22956511 (ang.).

- ↑ a b Parth J Parekh i inni, Successful treatment of Salmonella aortitis with endovascular aortic repair and antibiotic therapy, „BMJ Case Reports”, 2014, 2014, DOI: 10.1136/bcr-2014-204525, PMID: 24916982, PMCID: PMC4054513 (ang.).

- ↑ Maaike Spaltenstein i inni, A case report of CT-diagnosed renal infarct secondary to syphilitic aortitis, „BMC infectious diseases”, 17 (1), 2017, s. 520, DOI: 10.1186/s12879-017-2624-1, PMID: 28747159, PMCID: PMC5530486 (ang.).

- ↑ Dvora Joseph Davey i inni, Transient aortitis documented by positron emission tomography in a case series of men and transgender women infected with syphilis, „Sexually Transmitted Infections”, 2017, DOI: 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053140, PMID: 28866636 (ang.).

- ↑ Fernando Pivatto Júnior i inni, Aneurysm and dissection in a patient with syphilitic aortitis, „The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Brazilian Society of Infectious Diseases”, 21 (3), 2017, s. 349–352, DOI: 10.1016/j.bjid.2017.01.003, PMID: 28238625 (ang.).

- ↑ Laure Delaval i inni, New insights on tuberculous aortitis, „Journal of Vascular Surgery”, 66 (1), 2017, s. 209–215, DOI: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.11.045, PMID: 28254396 (ang.).

- ↑ J.S. Cargile i inni, Tuberculous aortitis with associated necrosis and perforation: treatment and options, „Journal of Vascular Surgery”, 4 (6), 1986, s. 612–615, DOI: 10.1016/0741-5214(86)90178-3, PMID: 3783836 (ang.).

- ↑ Stéphanie Rouiller i inni, Aortite à Clostridium septicum: rapport d’un cas et rappel sur les aortites infectieuses, „Revue Medicale Suisse”, 12 (534), 2016, s. 1703–1707, PMID: 28686395 (fr.).

- ↑ a b c Elizabeth A. Foote i inni, Infectious Aortitis, „Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine”, 7 (2), 2005, s. 89–97, PMID: 15935117 (ang.).

- ↑ Colin Y.L. Woon i inni, Extra-anatomic revascularization and aortic exclusion for mycotic aneurysms of the infrarenal aorta and iliac arteries in an Asian population, „American Journal of Surgery”, 195 (1), 2008, s. 66–72, DOI: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.01.032, PMID: 18082544 (ang.).

- ↑ Diane L. Murzin i inni, A case series of surgically diagnosed idiopathic aortitis in a Canadian centre: a retrospective study, „CMAJ open”, 5 (2), 2017, E483–E487, DOI: 10.9778/cmajo.20160094, PMID: 28641275 (ang.).

- ↑ a b Pravin Patil i inni, Giant cell arteritis: a review, „Eye and Brain”, 5, 2013, s. 23–33, DOI: 10.2147/EB.S21825, PMID: 28539785, PMCID: PMC5432116 (ang.).

- ↑ Dirk M. Nuenninghoff i inni, Incidence and predictors of large-artery complication (aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, and/or large-artery stenosis) in patients with giant cell arteritis: a population-based study over 50 years, „Arthritis and Rheumatism”, 48 (12), 2003, s. 3522–3531, DOI: 10.1002/art.11353, PMID: 14674004 (ang.).

- ↑ G.S. Kerr i inni, Takayasu arteritis, „Annals of Internal Medicine”, 120 (11), 1994, s. 919–929, PMID: 7909656 (ang.).

- ↑ Xue-Ping Wu, Ping Zhu, Clinical features of aortic dissection associated with Takayasu's arteritis, „Journal of Geriatric Cardiology : JGC”, 14 (7), 2017, s. 485–487, DOI: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2017.07.010, PMID: 28868078, PMCID: PMC5545192 (ang.).

- ↑ Dvora Joseph Davey i inni, Probable Syphilitic Aortitis Documented by Positron Emission Tomography, „Sexually transmitted diseases”, 43 (3), 2016, s. 199–200, DOI: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000411, PMID: 26859808, PMCID: PMC4748391 (ang.).

- ↑ S. Tyagi, U.A. Kaul, R. Arora, Endovascular stenting for unsuccessful angioplasty of the aorta in aortoarteritis, „Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology”, 22 (6), 1999, s. 452–456, PMID: 10556402 (ang.).

![]() Przeczytaj ostrzeżenie dotyczące informacji medycznych i pokrewnych zamieszczonych w Wikipedii.

Przeczytaj ostrzeżenie dotyczące informacji medycznych i pokrewnych zamieszczonych w Wikipedii.

Media użyte na tej stronie

The Star of Life, medical symbol used on some ambulances.

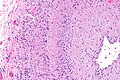

Star of Life was designed/created by a National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (US Gov) employee and is thus in the public domain.Autor: Nephron, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Micrograph of giant cell arteritis (also temporal arteritis). H&E stain.

See also

Autor: Yale Rosen from USA, Licencja: CC BY-SA 2.0

The pointer indicates the area of rupture of the aortic wall that led to the formation of the pseudoaneurysm which eventually ruptured. The thick fibrous wall of the pseudoaneurysm indicates that it had been present for a long time.

LAO angiographic of Takaysu Arteritis taken from MedPix. Image was taken by a staff member at Wilford Hall, thus it's in the public domain.

Under a very high magnification of 20,000x, this scanning electron micrograph (SEM) shows a strain of Staphylococcus aureus bacteria taken from a vancomycin intermediate resistant culture (VISA).

Under SEM, one can not tell the difference between bacteria that are susceptible, or multidrug resistant, but with transmission electron microscopy (TEM), VISA isolates exhibit a thickening in the cell wall that may attribute to their reduced susceptibility to vancomycin . See PHIL 11156 for a black and white version of this image. VISA and VRSA are specific types of antimicrobial-resistant staph bacteria. While most staph bacteria are susceptible to the antimicrobial agent vancomycin some have developed resistance. VISA and VRSA cannot be successfully treated with vancomycin because these organisms are no longer susceptibile to vancomycin. However, to date, all VISA and VRSA isolates have been susceptible to other Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved drugs.

How do VISA and VRSA get their names?

Staph bacteria are classified as VISA or VRSA based on laboratory tests. Laboratories perform tests to determine if staph bacteria are resistant to antimicrobial agents that might be used for treatment of infections. For vancomycin and other antimicrobial agents, laboratories determine how much of the agent it requires to inhibit the growth of the organism in a test tube. The result of the test is usually expressed as a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) or the minimum amount of antimicrobial agent that inhibits bacterial growth in the test tube. Therefore, staph bacteria are classified as VISA if the MIC for vancomycin is 4-8µg/ml, and classified as VRSA if the vancomycin MIC is >16µg/ml.